Opening hours

Main Library

Opening times for students

Term time

Monday-Friday 8am-1am

Saturday-Sunday 9am-1am

The Library is closed when the College closes for Christmas but remains open over vacations

Christmas Vacation and Long Vacation

Monday-Friday, 9am-5pm

Easter Vacation

Monday-Sunday, 9am-11pm

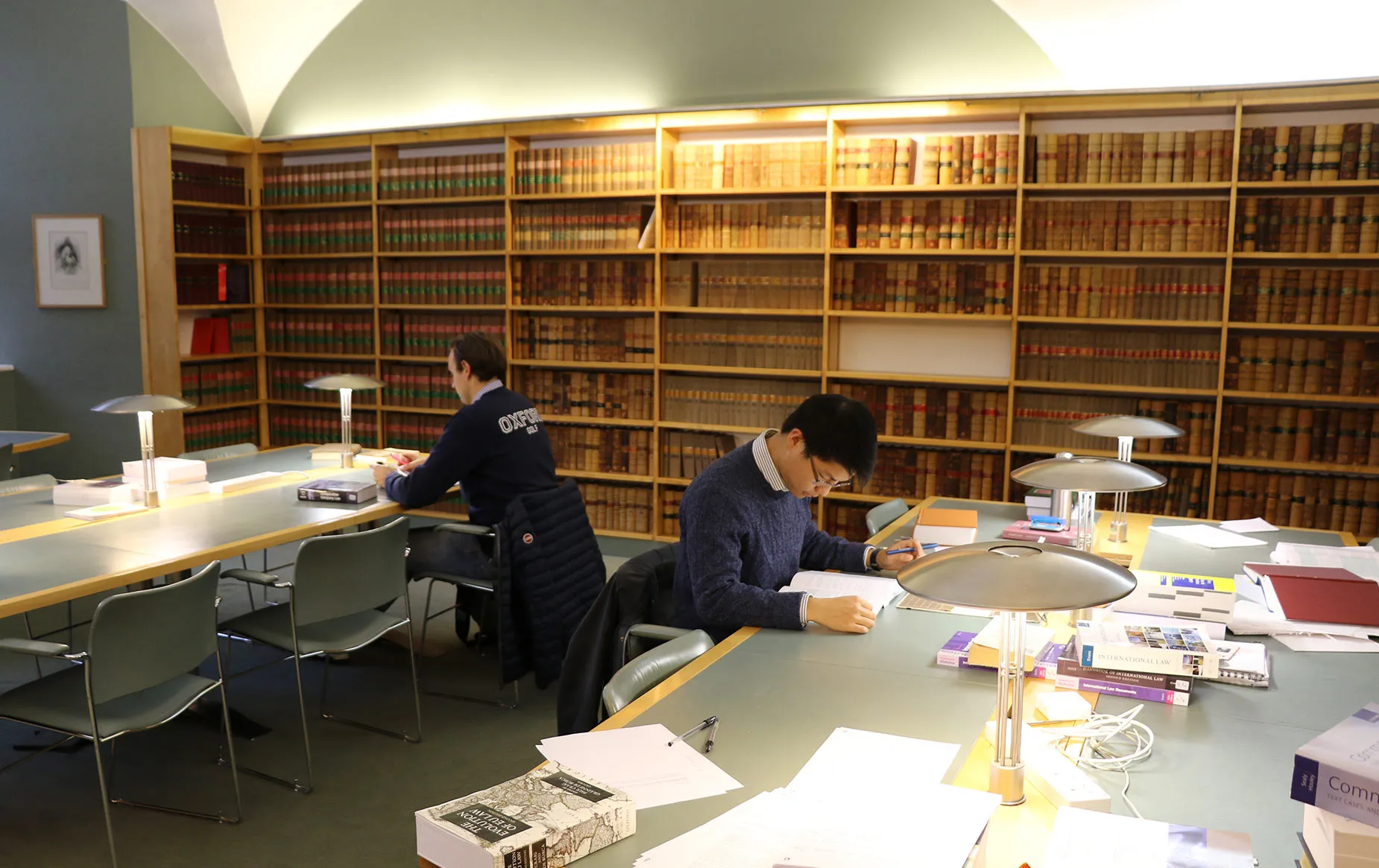

Burn Law Library

The Law Library is open from 8am to 11pm each day during Michaelmas Term. There will be no fob access outside these times.

Upper Library

The Upper Library is open Monday–Friday 10am–4.30pm.

Anyone wishing to visit the historic Upper Library should contact Library staff in advance (whether they are current members, alumni, or external visitors).

There is no step-free access to the Upper Library.