Breadcrumb

Christ Church academic explores postcolonial identity in the Caucasus and Central Asia

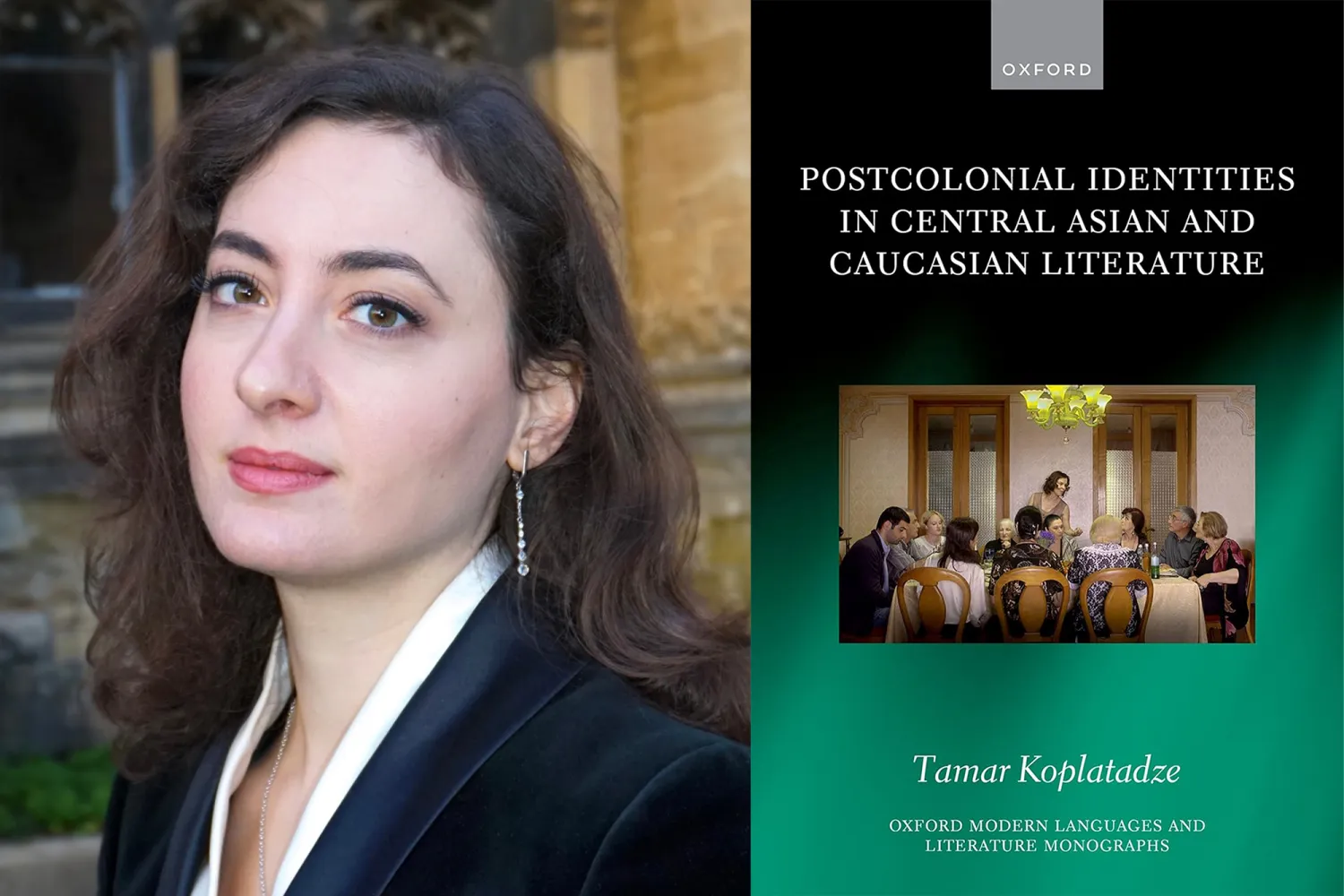

Dr Tamar Koplatadze, Associate Professor in Postsocialist Literature and Culture at Christ Church, has published a major new monograph with Oxford University Press examining postcolonial identity in the literatures of the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Postcolonial Identities in Central Asian and Caucasian Literature is the first large-scale and comparative study of post-Soviet literatures from the Caucasus and Central Asia, in any language, and explores how writers from Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and the five Central Asian states – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan – have reflected on the Soviet past and its lasting legacies.

Since the 2010s, both the Caucasus and Central Asia have witnessed a flourishing of their cultural scene.

Since the 2010s, both the Caucasus and Central Asia have witnessed a flourishing of their cultural scene.

‘Since the 2010s, both the Caucasus and Central Asia have witnessed a flourishing of their cultural scene, as the retreat of censorship and relative political stability freed up space for creative artists to share imaginative worlds that had been repressed for nearly a century,’ Dr Koplatadze observes. ‘Literature became the prime platform for reflecting on the Soviet past, and for determining the extent to which post-Soviet identity is a postcolonial one.’

Drawing on a wide range of contemporary fiction, the book demonstrates how these literatures engage with themes familiar to postcolonial studies – memory, gender, nationhood, language, censorship, migration, NGOs, utopianism and ecology. Many works revisit the traumas and taboos of the Soviet period. Uzbek memoirist Bibish, in The Dancer from Khiva (2004), recounts the exploitation of women and children in Soviet cotton farms and the racism faced by migrants in Moscow. Central Asian science fiction writers imagine posthuman futures shaped by ecological catastrophe, from the disappearance of the Aral Sea to nuclear testing in Semipalatinsk. Georgian novelist Nana Ekvtimishvili’s The Pear Field (2015) depicts the lives of orphans in post-Soviet Tbilisi as a legacy of ‘corruption, secrecy and survivalism’.

At the same time, Dr Koplatadze emphasises that these literatures resist simplistic binaries. ‘There is a great deal of humour in these literatures, and they transcend binary depictions of Russians as evil colonisers and the locals as helpless victims,’ she argues. Kazakh author Lilya Kalaus’s satirical The Fund of Last Hope (2013) lampoons both local and foreign NGO culture, while Armenian writer Narine Abgaryan’s Foreigner (2011) offers comic snapshots of post-Soviet life in Moscow.

As such, the book foregrounds the diversity of the post-Soviet space and its cultures. ‘To this day, Western popular imagination makes little to no distinction between Russia and the fourteen former Soviet republics, comprised of peoples of different histories, races, religions, cultures, traditions, languages, and alphabets,’ she notes. Moreover, the monograph challenges the long-standing narrative that treated the Soviet Union as a voluntary ‘union’ rather than an empire. ‘Until recently, history was written by the imperial centre, meaning that little was known of the colonial nature of the Soviet Union,’ Dr Koplatadze notes.

Ultimately, Dr Koplatadze hopes her work will broaden readers’ understanding of a region too often overshadowed in global literary conversations. ‘Fictional works from the Caucasus and Central Asia should be ranked alongside the great examples of postcolonial writing, and I hope more readers explore their unique charm, depth and variety,’ she says.

Postcolonial Identities in Central Asian and Caucasian Literature is published by Oxford University Press.

Other Christ Church news